My Hidden Extra Agenda

:Here are four ideas that, as soon as I first heard them, irrevocably

changed my worldview. If you haven't heard them yet, then I hope that

today they infect you the same way they did me.

In

political space, Left-Right is

a

slice, not an axis.

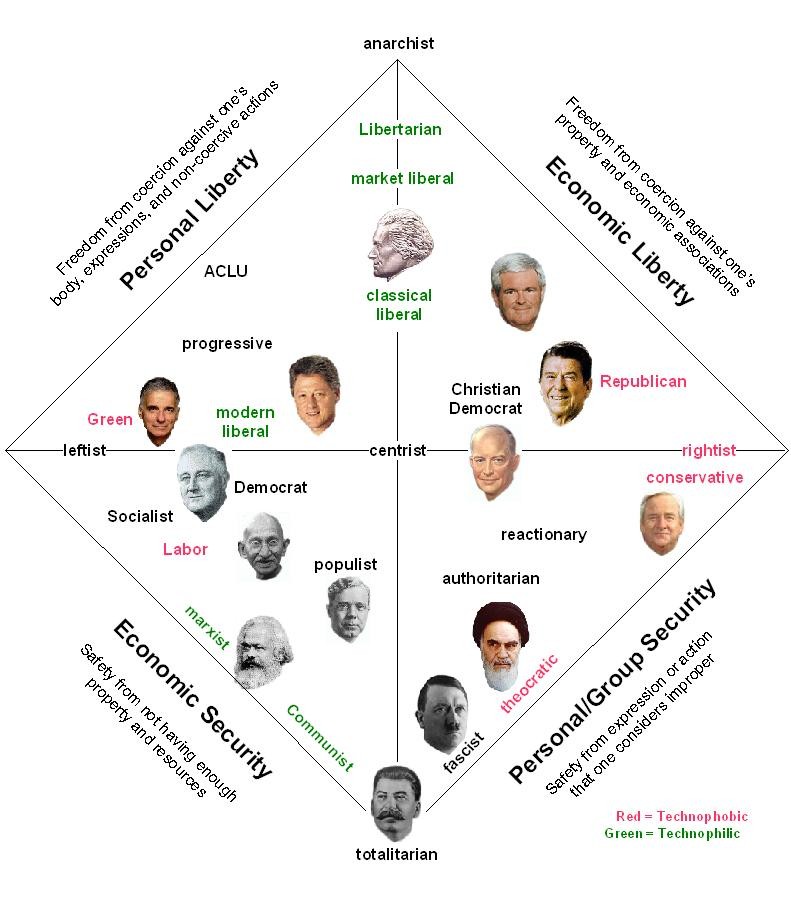

Left-right is not a true 1-D spectrum, or even an axis of 2-D political

space, but rather is a diagonal slice through 2-D

political space:

Rivalry and

Excludability define

what

goods the government should provide or manage.

Excludability is the ability of producers to detect and prevent

uncompensated consumption of their products. Rivalry is the

inability of multiple consumers to consume the same good.

A public good is a non-rival non-excludable good that

benefits almost everyone in a polity. Because public goods are not

excludable, they get under-produced. The pricing system cannot force

consumers to reveal their demand for purely non-excludable goods, and

so cannot force producers to meet that demand. Thus government should

produce non-excludable goods that aren't supplied by nature -- namely,

pure public goods. (Impure public goods

are those that are partly excludable -- those for which producers can

capture some but not all of the benefits that the goods provide.

Examples are education, technology development, landscaping,

broadcasting, and the

arts. Impure public goods need not be produced by government.)

A natural resource is any

rival non-excludable resource. Because natural resources are not

excludable but still rival, they get

over-consumed. Thus government should police the use of natural

resources, preferably by taxing resource use by the amount that the use

costs the rest of the polity.

A natural monopoly is any non-rival excludable good that

benefits almost everyone in a polity. Because natural monopoly goods

have high fixed costs and vanishing marginal costs, they cannot be

produced efficiently through market competition. Thus government

should regulate the provision of natural monopoly goods.

A private good is any rival

excludable good. Markets are able to manage their production and

allocate their consumption more efficiently than government can.

|

Rival

|

Non-Rival

|

Excludable

|

Private Goods

Efficiently produced and allocated by markets

- agriculture, minerals, artifacts

- labor, services

- land parcels

- rain and sunlight incident on land parcels

|

Natural Monopoly

High fixed costs, low marginal

costs => inefficient competition

- roads; water and sewage lines

- wired telecom networks (not content)

- power distribution (not generation)

- aggression deterrance; fire protection service

|

Non-Excludable

|

Natural Resources

Tragedy of the commons,

negative externalities => overconsumption

- atmosphere, bodies and streams of water, pollution sinks

- sunlight, wind, fish, game

- unowned land and space;

orbits

- electromagnetic spectrum; some namespaces

|

Public Goods

Free riders, positive

externalities

=> underproduction

- national defense

- scientific knowledge

- prevention of contagion, conflagration, flood

- anti-poverty safety net (assuming most

people favor charity)

|

All

environmental problems are

caused

by Negative Externalities.

In economics, an externality is a cost imposed or benefit

bestowed on a person

other than those who agreed to the transaction that created the cost or

benefit. Negative externalities

are costs such as pollution or overconsumption of natural resources. (Positive externalities are benefits

such as scientific discoveries and incremental technical

advances.)

In Economic

Instruments for Pollution Control and Prevention, Duncan Austin of

the World Resources Institute explains how market forces can be used to

correct for the market failure constituted by negative externalities:

Economic instruments, which aim to

control pollution by harnessing the power of market incentives, offer a more cost-effective, flexible and dynamic

form of regulation than conventional command-and-control

measures.

The underlying premise for economic instruments is to correct negative

externalities by placing a cost on

the release of pollutants.This will

internalize the externalities into the decision making process.

Placing a charge, or a fee, on every unit of effluent transforms the

manufacturer’s decisions regarding how much he

will produce, and how he will produce it. Now, the manufacturer must

minimize total production costs that consist not only of labor,

material, machinery and energy inputs, but also of the effluent output.

By adjusting

the charge level, or the cost attached to effluent outputs, the

regulator can induce a different degree of response from manufacturers,

and hence control the overall level of pollution. By changing the

charge level over time, the regulator has a relatively simple way of

ratcheting up standards.

The key benefit of economic instruments is that they would allow a given pollution target to be met

for lower overall cost than traditional regulations. Economic

instruments grant firms and individuals greater autonomy in deciding

how to meet targets; they create ongoing incentives for firms to design

new and improved abatement technologies ensuring that pollution control

becomes ever cheaper; they reduce the information burden on regulators;

and they provide potential revenue sources for state or federal

governments. In addition, economic instruments may provide greater

flexibility in dealing with smaller and diffuse emissions sources which

collectively contribute large amounts of pollution, but which until now

have been largely ignored in favor of controlling the pollution from

more obvious sources.

Economic instruments can create a system for pollution reduction that

achieves the same level of environmental protection for a lower overall

cost (or achieves more for the same cost). Under a command and control

approach, industries invest to meet the standard and then stop. In

contrast, placing a price on effluents creates a permanent incentive for environmental

improvement. Because every emission, or effluent, effectively

has a price attached to it, any profit-maximizing entity has an ongoing

incentive to make further reductions over time.

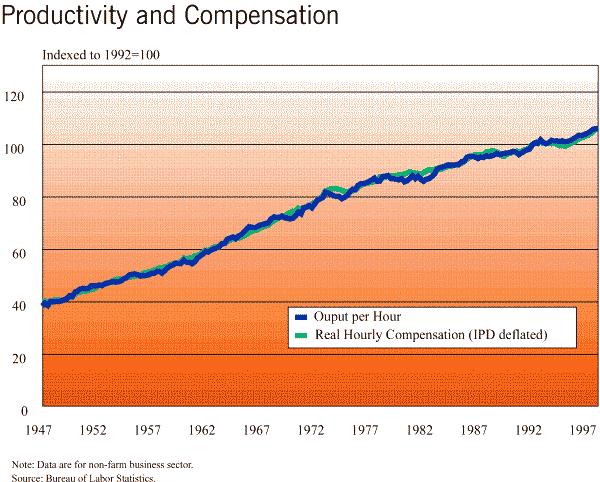

Wages

are determined by

productivity,

which is determined by capital.

Excerpts from Ten

Principles of the Economics of Capital by the National Center for

Policy Analysis:

Principle 1: Capital is the single most

important determinant of real wages. In a very real sense, the amount

of capital in our economy determines how much wage income we earn, even

if we do not personally own any capital. Workers’ wages and the capital

stock are inextricably linked. The only way that the real wages, and

thus the well-being, of workers can rise is if there is more capital

per worker.

Principle 2: More than 90 percent of the

benefits of a larger capital stock go to wage earners rather than

owners of capital. Many people believe that owners of capital get most

of the benefits capital creates. This turns out not to be the case. One

of the most surprising findings of the economics of capital is that the

overwhelming bulk of the extra income generated by capital accumulation

flows to people in their role as wage earners, rather than to the

owners of capital.

- For every additional dollar of income produced by a larger

capital stock, two-thirds goes to labor and only one-third to capital.

- After taxes and depreciation, the discrepancy is even greater;

labor receives 43.7 cents of each additional dollar of sales, while

owners of capital receive only 3.7 cents.

- In other words, workers get to keep $12 in after-tax wages for

every $1 of additional after-tax income to investors.

These facts have dramatic public policy

implications. In general, public policies that promote capital

accumulation primarily benefit wage earners, while policies that

discourage capital accumulation primarily penalize wage earners.

Principle 3: The amount of

capital is determined by investment. The nation’s capital stock is the

sum total of all of its capital goods. Because these goods lose value

over time, some level of investment is necessary to maintain the

capital stock at its current size. Beyond that level, additional

investment will cause the capital stock to grow, whereas less

investment will cause it to shrink.

Principle 4: The amount of

investment is determined by the real after-tax rate of return on

capital. The amount of physical capital available in our economy

depends on the willingness of people to invest in productive capital

goods. In making these decisions, investors are guided by the return

they will receive. The income to the investor must be adjusted for

inflation, depreciation, taxes and the riskiness of the investment.

After these adjustments are made, the investor can assess the after-tax

real rate of return on the investment.

Principle 5: Because of changes in investment

spending, the after-tax rate of return on capital tends to be constant.

Suppose something happens to cause the rate of return on capital to

rise above its historic average. There will be an increase in

investment, adding to the current stock of capital. As the capital

stock expands, the rate of return on capital will fall. Conversely,

when the rate of return on capital is below its historical level, there

will be a decrease in investment. As the capital stock shrinks, the

rate of return on capital will rise. Over the past 37 years, the rate

of return on capital in the U.S. economy has tended to be remarkably

stable — averaging about 3.3 percent per year.

Traditional neoclassical economics teaches

that the rate of return on capital must reflect people’s preference for

future rather than current consumption. In other words, to be induced

to save (forgo current consumption) and invest (with the expectation of

greater, future consumption), people must receive a minimum rate of

return on their investment. Because the time preferences of people are

unlikely to change very much over time, the rate of return on capital

will remain roughly constant.

Principle 6: Taxes on capital do not affect the

after-tax rate of return on capital but instead affect the amount of

capital available.

Although an increase in a tax on capital causes a

one-time reduction in wealth for owners of capital, it does not

permanently affect the future after-tax rate of return on capital.

After

such an increase, the after-tax rate of return on capital will be below

its historical average. Investors will respond by lowering their rate

of investment. The capital stock will shrink (relative to what it would

have been) until the rate of return reaches 3.3 percent. After the

adjustment has taken place, the owners of capital will receive the same

after-tax rate of return they received before the tax increase. This

does not mean that owners of capital will be indifferent to taxes on

capital. These taxes lower the after-tax future income stream on

existing capital assets. Thus a tax on capital lowers the value of

capital assets and makes current owners of capital less wealthy. For

any new purchase of an asset, however, capitalists will and can expect

the normal rate of return of 3.3 percent.